Let’s Talk Vaccines

Art: Aldous Massie

![]()

ost people I know have made up their minds regarding the COVID vaccines. Omicron is triggering a range of responses in them, some returning to isolation while others are trying to coast towards a sense of pre-pandemic normalcy. The level of dialogue between the dominant decision camps has also deteriorated to the point where many have become reactionary in the face of new or contrary information. Many seem to be making choices on different factors altogether and the level of patience and compassion for those opposite them appears to be in tailspin.

As I’ve been moderating discussion online throughout the pandemic I’ve felt increasingly obligated to be informed, but struggled to navigate the flows of misinformation, moral outrage, and ongoing waves of uncertainty. I realized I needed to organize and externalize all the most significant aspects from my own perspectives if I truly expected to enable better dialogue in each of the contexts I’ve found myself. I was still not prepared for the amount of difficulty navigating this information space, much less the frustrating lack of overviews and resources structured in ways which effectively summarize all the relevant factors.

My approach here seems effective thus far, but this page is still incomplete. I’m nowhere close to being the right person to translate scientific information and the data surrounding COVID is constantly changing. I’ve tried to include the most recent sources I could find and will be continually updating this as I get more feedback from readers. Keep in mind, the goal of this page is to share my notes and garner feedback. Do not take this as a static, fully balanced resource or as a case to convince anyone of anything.

This is NOT an attempt on my part to provide medical advice or suggestions. I have also not set out to include any analysis of the vaccine programs themselves, mandates, or the political aspects of COVID. I’ve set out framing this specifically around the question ‘What are the most relevant factors one should consider before getting vaccinated for COVID?’ Most people have already answered this question, but they asked it of themselves at some point (presumably) and the best answering of it should point us towards the most significant risks and benefits of vaccines, known or unknown. I’ve structured this around each of these factors, based on how effectively we can factor them or known they currently appear to be:

Knowns:

● Odds of exposure and infection

● Odds of negative outcomes

● Vaccine efficacy

● Vaccine risks

● Natural immunity

● Moral obligation

● Alternate forms of prophylaxis

● Barriers to understanding

Unknowns:

● Odds of reinfection

● Risks of an endemic

● Risks of variants

● Risks of long COVID

● Long-term risks of vaccines

● Future vaccines

● Barriers to good data

● Unknown unknowns

What are the odds of exposure & infection?

- Personalized

- Depends on many individual choices

- Difficult to factor

Potentials for exposure to COVID vary widely based on the contexts in which one might be exposed to a host, personal susceptibility, forms of contact, and numerous other factors. The type of variant and level of inoculum (i.e. infecting dose of the virus) also has significant impacts on the likelihood of infection and potential outcomes. The number of variables and elements of personal choice make this difficult to factor, but important to consider.

Source: What’s your risk of catching COVID? – Nature – December, 21 2020

Art: @alexthegreatphoto

What are the risks of negative outcomes?

- Outcomes are complex and still being studied

- Varies significantly based on personal factors such as age and comorbidities

The overall tallies of COVID hospitalizations in the United States do not differentiate based on severity of illness, making the outcomes related to survivable cases difficult to measure. The actual factors which constitute a severe case and how many patients fall into it is also still being studied and debated.

Case Fatality Rate

Death is the most negative outcome and easiest to measure, but still complex. The Case Fatality Rate (CFR) is the proportion of deaths amongst diagnosed cases of COVID and the most commonly reported measure. The CFR has changed over time, varies widely between countries, and still suggests considerable uncertainty over the exact CFR of COVID.

The median CFR for COVID in the United States is currently 1.63%. You can view the current CFR range for your country here. Median CFRs can still significantly under or over-represent the risk associated with a particular age group, gender, or individual.

For example, a female aged 30-39 may have a CFR of 0.26%, whereas a male 70-79 might have one of 19.71%. Calculating the individual risk of death involves many complex factors such as age, overall health, access to health care, and comorbidities. Age-stratified and other datasets which contain these nuances should be sought out when attempting to gauge individual levels of personal risk.

Infection Fatality Rate

Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) is the second most commonly reported statistic and attempts to estimate all of those with the infection, including undetected cases of the disease (asymptomatic or not tested). The CFR is highly dependent on the prevalence of testing and thus always higher than the IFR, but the IFR is likely to be a more complete measure of risk across all infections. Unfortunately, we do not currently have a good understanding of what proportion of COVID cases are asymptomatic and there are many other factors which make estimating the IFR for COVID difficult.

We could make a simple estimation of the IFR as 0.35%, based on halving the lowest boundary of the CFR prediction interval in Europe. However, the considerable uncertainty over how many people have the disease, the proportion asymptomatic (and the demographics of those affected) means this IFR is likely an overestimate.

In Swine flu, the IFR ended up as 0.02%, fivefold less than the lowest estimate during the outbreak (the lowest estimate was 0.1% in the first ten weeks of the outbreak). In Iceland, where the most testing per capita has occurred [for COVID], the IFR lies somewhere between 0.03% and 0.28%.

Taking account of historical experience, trends in the data, increased number of infections in the population at large, and potential impact of misclassification of deaths give a presumed estimate for the COVID-19 IFR somewhere between 0.1% and 0.35%.

Global COVID-19 Case Fatality Rates – Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine – Updated October 7, 2020

These estimates were made early in the pandemic and have likely changed, but I’ve had difficulty finding better instances of the latest measures of the IFR for COVID. It’s also important to note median IFRs and the actual IFRs will also vary significantly between age groups, regions, and those with comorbidities. For example, for a 30-40 year-old male with no comorbidities, one source would suggest they have an IFR of 0.05%. Another source would suggest they have an IFR 0.031%.

Excess Deaths

Excess deaths (or excess mortality) refers to the number of deaths from all causes during the pandemic compared to what we would have expected under normal conditions. This is a more comprehensive measure of the total impact of the pandemic and not as useful for evaluating personal risk, but relevant to consider when looking at the multitude of negative outcomes and estimating impacts of the pandemic. Due to the immensity of this measurement, it is also very complex and imprecise.

The official number of deaths caused by COVID-19 is currently 4.9 million. The Economist’s estimate of excess death is the most extensive I’ve seen and they consider there to be a 95% chance the excess deaths lie between 10.8 million and 20.1 million, as of November 24, 2021.

Sources:

COVID-19 Survival Calculator – Nexoid United Kingdom

Mortality Risk of COVID-19 – Our World in Data

Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Age Group – CDC

r/Coronavirus FAQ

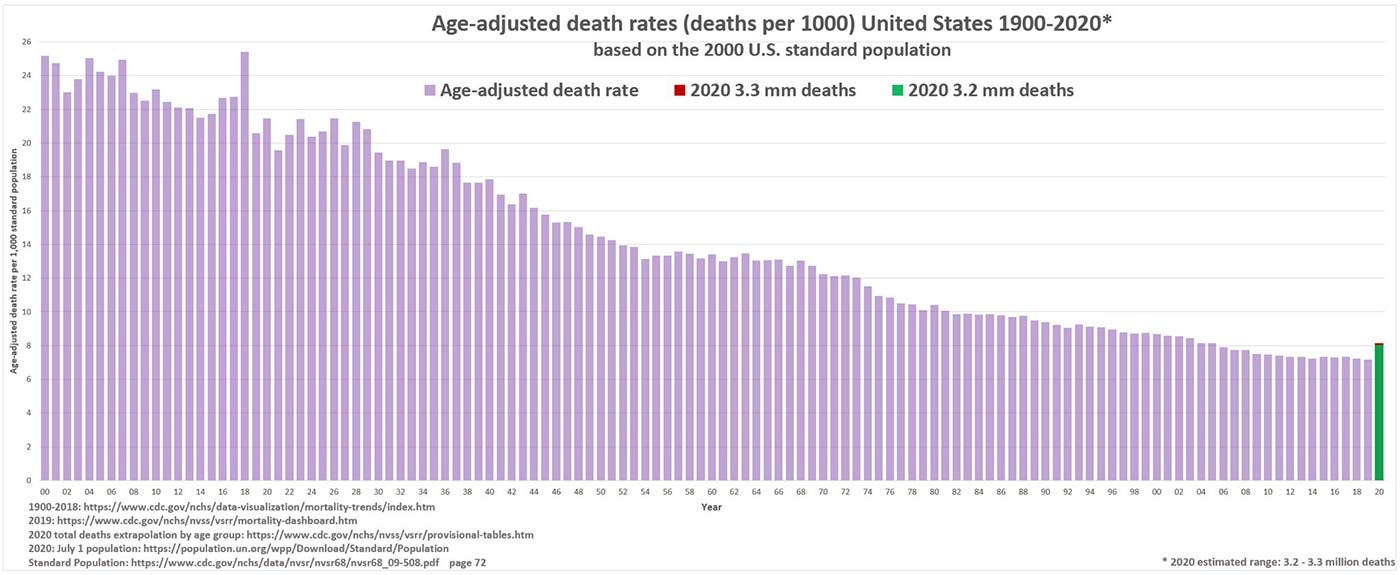

Age-Standardised Mortality Rate

Age-Standardised Mortality Rate (ASMR) is a statistical measure which shows the impact of the pandemic relative to previous years while taking population aging into account. There are many more old people in various age groups than there have been in previous years and the ASMR is not always considered when comparisons are made to death tolls from previous events such as World War II. This metric is less relevant on an individual level and more for maintaining a historical perspective on the overall impacts of the pandemic, relative to excess death measurements.

Comorbidities

A comorbidity is generally described as the presence of two or more diseases or conditions in the same person. Each condition is considered a comorbidity and sometimes can be present in the form of physical or mental conditions. An example would be if a person is suffering from asthma and diabetes or from both clinical depression and hypertension.

Comorbidities are generally non-communicable and contribute to nearly two-thirds of the annual deaths around the world (over 36 million deaths annually). Prominent forms of comorbidities are high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, arthritis, stroke, and cancerous conditions.

In regards to COVID, this study used data from more than 800 U.S. hospitals and looked at 4.8 million hospitalized patients, of whom 11% had COVID-19. Researchers found 94.9% had at least one underlying medical condition. Essential hypertension (50.4%), disorders of lipid metabolism (49.4%), and obesity (33.0%) were the most common. The strongest risk factors for death were obesity, anxiety, fear-related disorders, and diabetes with complication, as well as the total number of conditions. This can be complex data to assess, but is critical to factor. This is the best and most concise explanation of this particular paper and its implications I’ve seen.

Sources:

Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020–March 2021 – Published July 1, 2021

What are comorbidities: How do they impact Coronavirus? – Narayana Health – June 19, 2020

CDC Data is surprising – Peak Prosperity with Chris Martenson – July 27, 2021

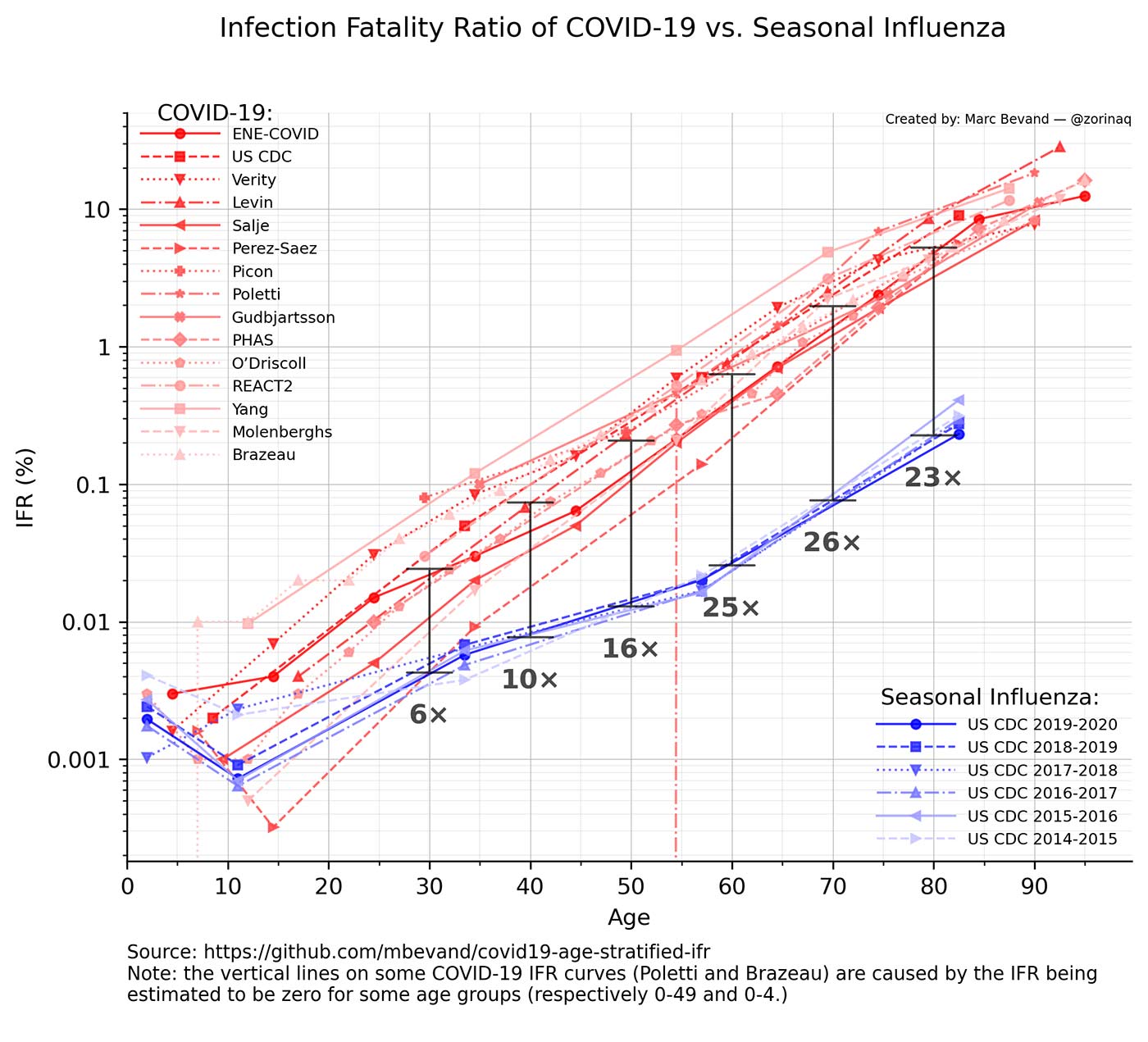

Comparisons to Influenza

Many have compared aspects of COVID-19 to the impacts of the seasonal influenza (the flu). They share several common clinical and epidemiological characteristics, but a one-to-one comparison of CFRs is not reliable and potentially dangerous. For example, if a comparison is applied to countries with a strong containment of the COVID-19 pandemic, the severity of COVID-19 may be underrated. On the other hand, presenting COVID-19 as having much higher fatality rates can underrate the severity of the seasonal flu.

The severity and risks of COVID should be able to be factored well enough on their own, but we may still wish to be aware of the differences and similarities as much as they can potentially be made, especially since they are still commonly compared in the media with varying degrees of nuance.

In terms of disease, seasonal influenza and COVID-19 are both contagious respiratory illnesses, but are caused by different viruses. COVID-19 seems to spread more easily and can cause more serious illnesses in some people. COVID-19 can also take longer before people show symptoms and people can be contagious for longer. COVID-19 is also an ongoing pandemic, whereas influenza is largely caused by endemic strains of several influenza virus subtypes that have circulated over decades. These viral strains cause more or less severe epidemics annually.

Deaths due to COVID-19 and influenza are not counted in the same way, which makes comparing CFRs difficult. Each death due to influenza in the U.S. does not have to be reported, so there is never a direct count. Each flu season, the CDC estimates deaths from the flu based on in-hospital deaths and death certificate data. Conversely, each death due to COVID-19 is being recorded.

This is the most granular comparison I’ve seen of IFR between COVID-19 and seasonal influenza which pulls data from multiple studies. It was last updated June 20, 2021.

Sources:

Similarities and Differences between Flu and COVID-19 – CDC

How Do COVID-19’s Annual Deaths and Mortality Rate Compare to the Flu’s? – GoodRx – August 27, 2020

Why comparing COVID-19 and seasonal influenza fatality rates is like comparing apples to pears – April 6, 2021

Comparing COVID-19 to seasonal influenza – Marc Bevand – Updated June 20, 202

Comparisons to other pandemics

It’s very difficult to make comparisons between pandemics as they all develop within specific circumstances and the underlying nature of viruses varies significantly. For the sake of general comparison, the global case rates and Case Fatality Rates (CFR) for these past pandemics are as follows:

- 1918 influenza (H1N1): 50 million – 2-3% CFR

- Avian influenza A (H5N1 and H7N9): 649 cases – 60% CFR and 571 cases – 37% CFR

- Ebola: Over 30,000 cases – Average 50% CFR

- MERS-CoV: 2,502 cases – 34% CFR

- SARS-CoV: 8,422 cases – 15% CFR

- SARS-CoV-2: 261,000,000 cases – Currently 1.99% CFR (World)

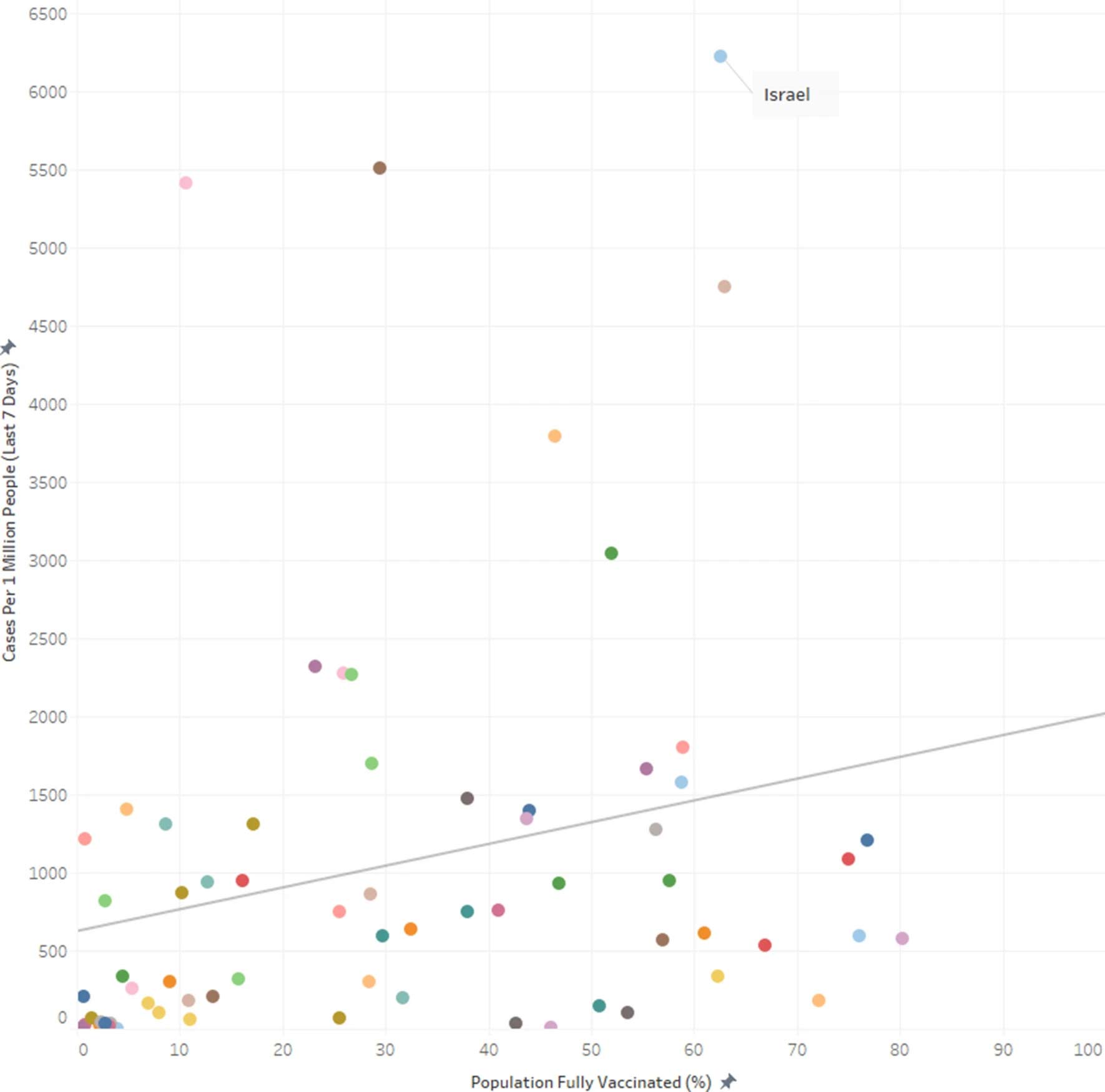

Comparisons between percentage vaccinated and COVID cases

Another alternative measure of efficacy involves examining the relationship between vaccinations and their effect on new COVID cases over time. One attempt to do this by a Harvard professor has been referenced broadly in an attempt to show the ineffectiveness of the COVID vaccines globally. This is worth addressing due to how widely it has been shared and to show the limitations of this approach.

This graph from the study showed the relationship between cases per one million people over seven days in September 2021 and the percentage of population fully vaccinated across 68 countries.

The study was submitted to the European Journal of Epidemiology as correspondence or a letter, not an academic paper. The first author, Sankaran Venkata Subramanian, is a Doctor of Geography and Professor of Population Health and Geography at Harvard University. His co-author, Akhil Kumar, is listed as a student from a high school in Ontario, Canada.

The study only compared two basic variables in each country, COVID cases and percentages of people fully vaccinated. Cases are an imperfect metric which depend on the prevalence of testing and if not performed cannot give an accurate representation of actual cases within a country. Relaxed restrictions, the Delta variant, waning vaccine immunity, natural immunity, timing of vaccine rollouts, population densities, and quality of healthcare were all unfactored. Numerous variables make simple population-level comparisons such as these misleading and incomplete. It’s also important to note that the primary goal of COVID-19 vaccines is not to prevent infections completely but to minimize the risk of severe disease and death. These have separate measures of efficacy, as described previously.

Subramanian, the primary author, later said his findings have been misinterpreted.

“Concluding from this analysis that vaccines are useless is misleading and inaccurate. Rather, the analysis supports vaccination as an important strategy for reducing infection and transmission, along with handwashing, mask-wearing, proper ventilation and physical distancing.”

COVID-19 “surges among most vaxxed communities, says Harvard study.” – Politifact – October 17, 2021

A variety of people have offered detailed criticisms of the paper. These are the most relevant I’ve found:

- Health Nerd, an Epidemiologist and writer, did a good, brief analysis of the other issues with the paper.

- Kristen Panthagani is a writer and MD-PhD who gave some good additional criticisms.

- Carl de Boer is an Assistant professor at the BME UBC and also offered his criticisms as well.

Sources:

Fact Check: Author Of Article Does NOT Question Positive Effects Of Vaccines The Way Commentary Spun From It Does – Lead Stories by Sarah Thompson – October 20, 2021

European Journal of Epidemiology Publishes Hot Garbage – Chatters – October 4, 2021

Claims that a Harvard study showed COVID-19 vaccines are ineffective misrepresent the authors’ conclusions, fail to account for the study’s limitations – Health Feedback – October 17, 2021

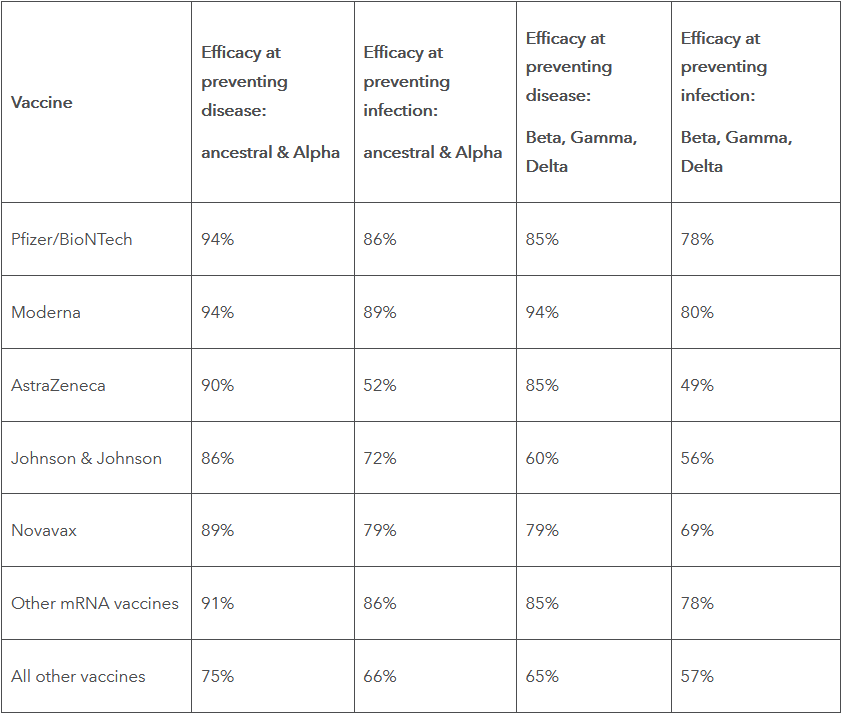

How effective are the vaccines?

- Measurable, but still being studied

- Efficacy wanes and boosters are necessary

- Vaccines differ significantly

- New vaccines are still being developed

According to CDC definitions, immunity means protection from an infectious disease. If you are immune to a disease, you can be exposed to it without becoming infected. A vaccine is a preparation that is used to stimulate the body’s immune response against diseases. Vaccines are not necessarily 100% effective or provide total immunity to a disease.

Efficacies for the COVID-19 vaccines are most commonly stated (e.g. in the news) only in terms of how well they reduce the severity of symptoms of the disease (COVID-19). There are separate measures of efficacy for how effective each vaccine is against preventing disease versus preventing infection.

The best table I’ve seen for the multiple efficacy estimates has been assembled here by The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) from a variety of peer-reviewed publications, reports, and other sources. It was last updated August 9, 2021.

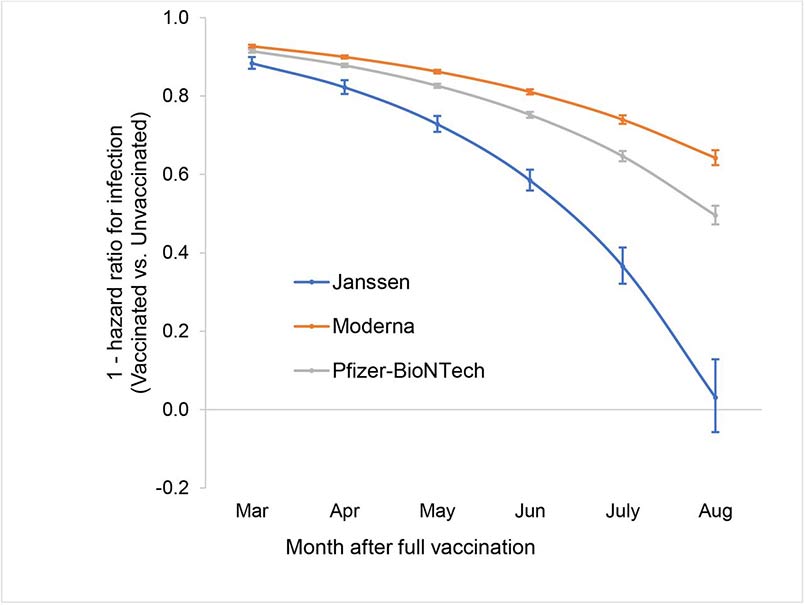

Efficacy in terms of preventing infection has been found to wane over time. A recent study followed 620,000 U.S. Veterans from February 2021 to August 2021 to measure the efficacy of the three major vaccines in the US for preventing infection.

Over this period, efficacy for J&J went from 88% to 3%, for Pfizer-BioNTech 91% to 50%, and for Moderna 92% to 64%. A much larger study over a similar period found similar declines for Pfizer–BioNTech, from 88% to 47% after five months. Effectiveness against hospital admissions for infections with the delta variant for all ages was still high overall (93%) up to 6 months. Additionally, a recent study from Sweden (preprint) showed similar progressions for Pfizer–BioNTech from 92% at day 15-30, to 47% at day 121-180, and from day 211 and onward no effectiveness could be detected (23%).

Sources:

Immunization: The Basics – CDC

Why did CDC change its definition for ‘vaccine’? Agency explains move as skeptics lurk – Miami Herald – September 27, 2021

Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccination Against Risk of Symptomatic Infection, Hospitalization, and Death Up to 9 Months: A Swedish Total-Population Cohort Study – The Lancet – October 25, 2021

Efficacy of preventing transmission

“We’re concerned about the false sense of security that vaccines have ended the pandemic and people who are vaccinated do not need to take any other precautions. Vaccines save lives but they do not fully prevent transmission. Data suggests that before the arrival of the Delta variant, vaccines reduced transmission by about 60 percent. With Delta, that has dropped to about 40 percent.”

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General – November 24, 2021

Another measure of efficacy is the rate at which vaccines prevent transmission of the virus. Multiple large studies have shown vaccinated individuals are less likely to infect others, but the exact rates of transmission and differences inherent to the most recent variants are still being studied.

It’s important to understand vaccines are effective at preventing infection which then contributes to the overall likelihood of transmission occurring in the first place. The measure of efficacy for preventing infection and transmission both vary based on a variety of factors and it can sometimes be difficult to tell if someone is stating the rate of transmission by itself or combined with the reduced rate of infection to present a form of overall efficacy against transmission. The latter will always be larger and relevant, but it is important to distinguish the numbers and understand where they are combined..

A household study in the Netherlands of 4,921 cases from August to September, 2021 found the effectiveness of the vaccines at reducing transmission of the Delta variant was 40% against vaccinated contacts and 63% against unvaccinated contacts. The authors previously found an effectiveness of 73% against transmission to unvaccinated household contact for the Alpha variant.

A study of 814,806 Swedish families from April 15 to May 26, 2021 found nonimmune families with one immune family member had a 45% to 61% lower risk of contracting COVID-19. The study considered individuals who acquired immunity from either previous infection or full vaccination. Each person with immunity was then matched to someone without immunity into another family.

A study from Israel used data from June 2020 to March 2021 on 1,275,015 households. Their estimates of efficacy against transmission were 41.3%

Further Reading

What risks are associated with the vaccines?

- Safety signals exist, but require more study

- Risks exist, but are small

- Liability for adverse events rests largely on the individual

Over 230 million people have received at least one vaccine dose in the United States through November 22, 2021. The CDC states the COVID-19 vaccines are safe and under intense safety monitoring.

“To date, CDC has not detected any unusual or unexpected patterns for deaths following immunization that would indicate that COVID vaccines are causing or contributing to deaths, outside of the three confirmed deaths following the Janssen vaccine.”

Unnamed CDC Spokesperson speaking to Reuters – October 4, 2021

VAERS

Medical professionals and pharmaceutical manufacturers are mandated to report adverse events to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). VAERS is used to report side effects related to vaccinations in the United States and the only pharmacovigilance database used by FDA and CDC which is accessible to the public.

A report to VAERS does not definitively mean a vaccine caused an adverse event. Anyone can submit a report to VAERS, including healthcare professionals, vaccine manufacturers, and the general public at any time. VAERS is called the “early warning system” because it is intended to reveal early signals of problems, which can then be further evaluated.

654,412 reports of adverse events have been made for the COVID vaccines in the United States through November 12, 2021. VAERS data is still imperfect at best and under-reporting and under-recording are significant issues. More study is needed to effectively determine the implications of the VAERS data and the current signals within the system.

Steve Kirsch, Jessica Rose, and Mathew Crawford claim their analysis (last updated November 1, 2021) of VAERS data shows it is likely over 150,000 in the U.S. have been killed by the COVID vaccines. The best analysis of their claims I’ve seen has been through these two articles:

Debunking Steve Kirsch’s latest claims about Covid vaccine deaths by The Gift of Fire – October 26, 2021

Underreporting and Post-Vaccine Deaths in the VAERS Explained by Shin Jie Yong – July 27, 2021

Sources:

Fact Check-COVID-19 vaccines do not kill more people than they save – Reuters – September 23, 2021

Estimating the number of COVID vaccine deaths in America – By Steve Kirsch, Jessica Rose, Mathew Crawford – Updated November 1, 2021

Safety Studies

Three large studies regarding vaccine safety have been published. These three studies have been particularly valuable since they had proper control or comparison groups. Science writer Shin Jie Yong did an excellent summary of them here which is worth reading for seeing the results of these in full detail and with better analysis. I attempt to summarize his analysis of each below.

US Study

One study from September 2021 published in JAMA reviewed data in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), which provides the CDC with medical data on vaccination histories and health outcomes. VSD is a collaborative project between CDC’s Immunization Safety Office and nine health care organizations and one of the best databases for reviewing adverse events post-vaccination since it has access to actual medical records.

Researchers examined 23 types of adverse events in 6.2 million people who received either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine between December 2020 to June 2021. The study compared vaccinated people at 0–21th vs. 22–42th days after vaccination.

Among the 23 adverse events investigated, only two reached statistical significance. One was anaphylaxis with an excess of about 5 cases per 1 million doses. The second was the younger subgroup of myocarditis/pericarditis. Specifically, 12–39-year-olds at days 1–21 of vaccination had a 9.8-times increased risk of myocarditis or pericarditis compared to those at days 22–42 of vaccination. This gave an excess of 6.3 cases per million doses.

Israel Study

An Israel study from August 2021 matched 884,828 people vaccinated with Pfizer in Israel with an additional pair of unvaccinated individuals. Both groups were nearly identical in age, sex, residence, socioeconomic status, population sector, and number and type of preexisting chronic conditions. They investigated 25 types of adverse events which might have occurred within 21 days of the first or second dose of the vaccine. Results revealed that compared to the unvaccinated group, the vaccinated group had higher risks of:

- Myocarditis (inflamed heart muscle): RR = 3.24-times increased risk; RD = 2.7 excess events per 100,000 persons. For this adverse event, 90% of the cases were males aged 20–34 years.

- Lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes): RR = 2.43-times increased risk; RD = 78.4 excess events for 100,000 persons.

- Appendicitis (swollen appendicitis): RR = 1.4-times increased risk; RD = 5 excess events per 100,000 persons.

- Herpes zoster infection (skin rashes or shingles): RR = 1.43-times increased risk; RD = 15.8 excess events per 100,000 persons.

Risk Ratio (RR) is relative (e.g., 5%÷10% = ↓ 50% or 0.1%÷0.2% = ↓ 50%), whereas Risk Difference (RD) is absolute (e.g., 5%−10% = −5% or 0.1%−0.2% = −0.1%).

UK Study

In a study from August 2021 researchers from the U.K. performed a population-based, observational study different from the Israel and U.S studies. Researchers used data from 29 million individuals in England who received their first doses of either the AstraZeneca (19.6 million) or Pfizer (9.5 million) vaccines. Based on the blood clots concerns surrounding vaccines it investigated if seven specific adverse events could be linked to the vaccines.

The AstraZeneca vaccine was associated with a small increased risk of thrombocytopenia, venous thromboembolism, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), and other rare blood clotting disorders. The Pfizer vaccine with arterial thromboembolism, CVST, and ischaemic stroke. The relative risks were small (less than two times). Generally, in observational studies, a less than 2-times difference is unlikely to override the effects of residual, uncontrolled confounding factors such as genetics, socioeconomic status, or health awareness. There was a 4-times increased relative risk of CVST. In this study overall, there were 75 CVST cases out of the 29.1 million vaccinated persons.

Overall

Each of these studies detected risks which were not observed in the previous clinical trials for the mRNA vaccines. Although, observational studies such as these still cannot effectively prove causation without randomized control groups. Some of the excess events — especially myocarditis, pericarditis, and blood clot disorders — have hospitalized people and a small proportion of those hospitalizations may have even ended up in death, as the U.K. study found. These studies also only examined short-to-medium-term risks of vaccines.

“After nearly a year since mass vaccination began, we now have a better understanding of the mRNA (and DNA) vaccine’s safety profile. Yes, those vaccines have risks. But like any medical intervention, such risks must be weighed against the risks of infection or benefits of vaccination. This risk-benefit assessment may differ substantially in some people, but for the overwhelming majority, vaccines are the more reasonable choice.”

Shin Jie Yong – Editor of Microbial Instincts

Sources:

Adverse events surveillance after 11.8 million COVID mRNA vaccine doses by Skeptical Raptor – September 7, 2021

mRNA Vaccine Safety and Risks: A One-Year Update From the U.S., U.K., and Israel by Shin Jie Yong – September 12, 2021

COVID-19 Vaccine for Minors: All The Possible Benefits and Risks Explained by Shin Jie Yong – June 2, 2021

Menstrual Disruptions After COVID-19 Vaccines: What the Literature Says by Shin Jie Yong – November 18, 2021

Liability

In early 2020, Health and Human Services (HHS) invoked the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act to provide legal protection for the companies making the vaccines. The protection lasts until 2024. This means the vaccine manufacturers cannot be sued for damages in court over injuries related to COVID-19 vaccines. The intent of the law is to urge manufacturers to quickly gear up to combat a possible pandemic without fear of lawsuits. Manufacturers have similar clauses built into their contracts outside the United States as well, shielding them from various potential risks indefinitely.

Individuals can seek compensation from the U.S. government through the Countermeasures Injury Compensation Program (CICP). Although, the bar for compensation is very high and claims are more often denied. The CICP has rejected a majority of the compensation requests made since the program began 10 years ago. Of the 499 claims filed, the CICP has compensated only 29 claims, totaling more than $6 million and as of October 31, 2021 the CICP has not compensated any COVID-related claims.

Sources:

Feds Pay Zero Claims For COVID-19 Vaccine Injuries/Deaths by Adam Andrzejewski – Forbes – November 4, 2021

You can’t sue Pfizer or Moderna if you have severe COVID vaccine side effects. The government likely won’t compensate you for damages either – CNBC – December 17, 2020

The false claim that the fully-approved Pfizer vaccine lacks liability protection – The Washington Post – August 30, 2021

How strong is natural immunity?

- Likely comparable to or more efficacious than vaccines

- Not everyone will have or obtain natural immunity

The largest study on natural immunity covered the entire country of Israel from June 1, 2020 to March 20, 2021. This covers the period when the alpha variant was dominant and Pfizer was the exclusive vaccine used. Previous infections were 2-10 months old, and vaccinations were 0-3 months old. The more recent vaccination was 93% effective against infection, 94% against hospitalization, 94% against severe illness, and 94% against death. Older cases of natural immunity were 95% effective against infection, 94% against hospitalization, and 96% against severe illness. In this study, ‘older natural immunity was shown to be equivalent to recent vaccination.

Two Time-Matched Delta Studies

Two additional studies covered the time period when delta became dominant, which is important because delta may evade immunity from vaccines more effectively than natural immunity. One was done in Israel, and the other in the United States. On the whole, the US study was designed to replicate the Israeli study by covering the same time period, focusing on the delta variant, and matching people according to their demographics, risk factors, and when they got infected or vaccinated. In both cases, previous infections were drawn from electronic medical records.

In the Israeli study, natural infection offered 13-fold better protection against infection, 27-fold better protection against developing symptoms, and 8-fold better protection against hospitalization. When the Israeli study used a group that was twice as big but not matched for the time of vaccination or infection, natural immunity was 6-fold more protective against infection and 6.7-fold more protective against hospitalization.

At first glance, the US study appears to suggest the vaccines work better than natural immunity for people over 65, but not for younger people. For seniors, they offered 66% lower risk of infection and hospitalization and 95% lower risk of death. However, the study covered June through August of 2021, and delta didn’t reach close to 100% of infections until July and August. By August, natural immunity had become equivalent to Moderna and superior to Pfizer.

Sources:

Natural Immunity Vs. Vaccination by Chris Masterjohn, PhD – October 29, 2021

Lasting immunity found after recovery from COVID-19 – NIH – January 26, 2021

Comparing SARS-CoV-2 natural immunity to vaccine-induced immunity: reinfections versus breakthrough infections – August 25, 2021

Are there moral obligations?

- Controversial and Complex

- Consideration requires an existing moral framework

- Comparable impacts associated with COVID-19 are still far from socially acceptable

An individual’s moral obligation to get vaccinated and the right of the state to enforce vaccination are separate issues. Based on the task at hand I’ll only be focusing on the former. I will also assume there is no common desire to or case for knowingly infecting others with COVID, so the risks or chances associated with doing so will not be factored here.

Individuals have unilateral moral authority over what happens to their bodies. Although, our immunity to disease is a shared resource. For the same reasons it would be wrong to risk poisoning drinking water (a shared resource) it would be morally wrong to risk endangering our collective immunity to a disease. The specific level of normalized or socially accepted risk is variable depending on the disease and region, but the level of risk is potentially factorable based on how we are choosing to expose ourselves to others, in what contexts, and what the risks associated with the choices are for exposure.

Accepted Levels of Risk

For the sake of comparison, we have largely normalized a range of risks associated with seasonal influenza, which kills between 12,000 and 52,000 Americans each year, according to CDC estimates. We’ve normalized this particular level of mortality for this disease in the past without taking certain additional measures to lower it, such as wearing masks or mandating flu vaccines. Regardless, we should still presume people will disagree on what constitutes an ‘acceptable’ level of mortality for any disease, including COVID-19.

“I am not prepared to say what the appropriate benchmark is yet, but it certainly is much, much lower than where we are, and much closer to where the flu is.”

Jen Kates, Director of Global Health & HIV Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation

Asymptomatic Infection

The rates of asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 play a significant role in our determination of risks within moral contexts, since they represent the chance we might unknowingly infect someone without intending to do so. Although, there are some complexities involved in determining this rate as the notion of asymptomatic can be defined in varying ways. Some would define it as someone testing positive, but showing no explicit COVID-19 symptoms, even though other symptoms could be present. Scientific stringency might argue an asymptomatic case is one with SARS-CoV-2 infection as determined by PCR and/or serology but with no symptoms whatsoever for the duration of infection.

Meta-analyses and studies of large cohorts have shown between 20–40% of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic. However, with looser criteria of ‘no COVID-19-related symptoms’, some studies, such as a survey of 9,500 residents of Wuhan, place the proportion of asymptomatic cases above 80%.

An important aspect of this data is whether there are differences between age groups, especially the often-quoted assumption that children and adolescents are more likely to be asymptomatic following infection. Early data suggests asymptomatic disease is inversely correlated with age, meaning asymptomatic cases are common in younger people. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 350 studies concluded asymptomatic presentation in elderly people occurred in 19.7% of cases, compared with 46.7% in children.

Effects of Vaccines on Transmission Rates

Researchers generally agree vaccinated people spread the virus less overall, but the actual extent of the reduction is still undermined. The Atlantic had the best recent sampling of perspectives from various sources regarding this I’ve seen thus far.

“I think that the jury is still out about the extent to which vaccination might reduce the risk of transmission, but we do know that transmission does occur,” Lisa Maragakis, the senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System, told me. “I wouldn’t say it’s low [risk].” She alluded to data showing similar viral loads in vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

How Easily Can Vaccinated People Spread COVID? by Yasmin Tayag – The Atlantic – November 8, 2021

Unknowns

The extent to which asymptomatic cases can transmit the virus remains a subject of debate. The differences between specific variants also requires more research. The extent to which asymptomatic disease leads to long COVID, and the quality, quantity, and durability of immune priming required to confer subsequent protection are also unknown. The high level of nuance and limits of current understanding regarding these factors make defining quantifiable risks difficult.

Art: KIDS

Moral Calculations

An individual can take a wide range of actions which may or may not contribute to or diminish collective immunity. I would venture a specific action, knowingly taken, is as immoral as it detracts from collective immunity if it creates a significant risk of exposure to others, exceeds pre-existing expectations of risks compared to other diseases, and occurs within a context where other individuals present cannot sufficiently protect themselves from exposure (or avoid being present). The specific level of risk would then have to be compared to the the current spectrum of available methods for prophylaxis (including none at all) and against current social expectations within that specific setting.

This is a crude model, only my personal perspective, and still highly dependent on the complex math and data available related to each of the various factors explored here. I share this mainly to invite criticism, as this specific factor is complex and I’ve had difficulty finding nuanced explorations of it elsewhere.

Sources:

The immunology of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: what are the key questions? – October 19, 2021

There are plenty of moral reasons to be vaccinated – but that doesn’t mean it’s your ethical duty – The Conversation – by Travis N. Rider – April 20, 2021

Vaccine Q&A: Do I Have a Moral Obligation to Wear a Mask or Get Vaccinated? – Matt Shipman – September 20, 2021

How you’ll know when COVID-19 has gone from “pandemic” to “endemic” by Sigal Samuel – Vox – October 22, 2021

Are there alternate forms of phrophylaxis?

- No alternatives exist comparable to vaccines

- Singular strategies have significant limitations

Prophylaxis means prevention of disease. There are multiple types of prophylaxis which include strategies for preventing a disease from getting worse to preventing over-treatment. Vaccines are one form of prophylaxis, but they cannot be used to treat an existing case of COVID-19. Masks, social distancing, and hand-washing are also important forms.

Art: @sarashakeel

Risk Reduction

While this page represents an attempt to address the data related specifically to the layer of risk reduction provided by vaccines, they should not be viewed as the only relevant form, nor as shielding us from every form of risk in every scenario. The Swiss Cheese model is the most effective I’ve seen for communicating the various methods for overall risk reduction and importance of not relying on a single strategy.

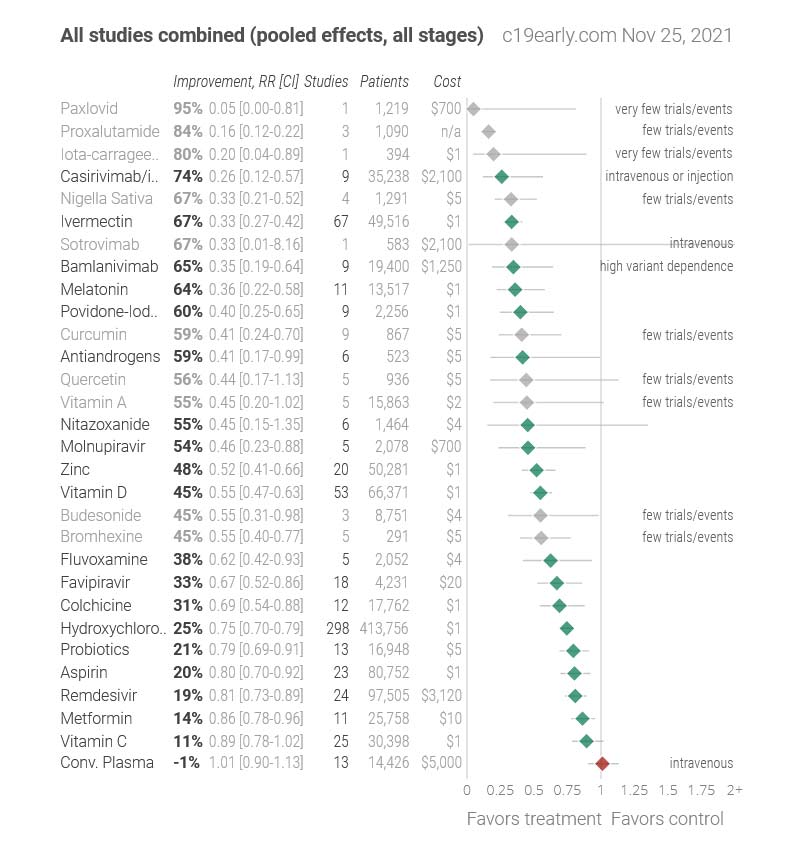

Early Treatment Data

Many forms of early treatment for COVID-19 are currently being studied. Early treatment only occurs after one has gotten COVID, but some forms have shown significant benefits as prophylactics as well. For example, Ivermectin has shown some improvement for early treatments and prophylaxis, but the numbers are highly debated.

Vitamin C, Vitamin D, and Zinc are the most common I’ve seen discussed online. The NIH’s summary of recommendations regarding these was last updated April 21, 2021 and indicates there is insufficient evidence for their panel to recommend either for or against their use for the treatment of COVID-19.

C19early.com and Ivmmeta.com have the most comprehensive overviews of all the studies and information related to these early treatments and ivermectin I’ve found. It’s worth noting this disclaimer is listed on the site:

“Treatments do not replace vaccines and other measures. All practical, effective, and safe means should be used. Elimination is a race against viral evolution. No treatment, vaccine, or intervention is 100% available and effective for all variants. Denying efficacy increases the risk of COVID-19 becoming endemic; and increases mortality, morbidity, and collateral damage.”

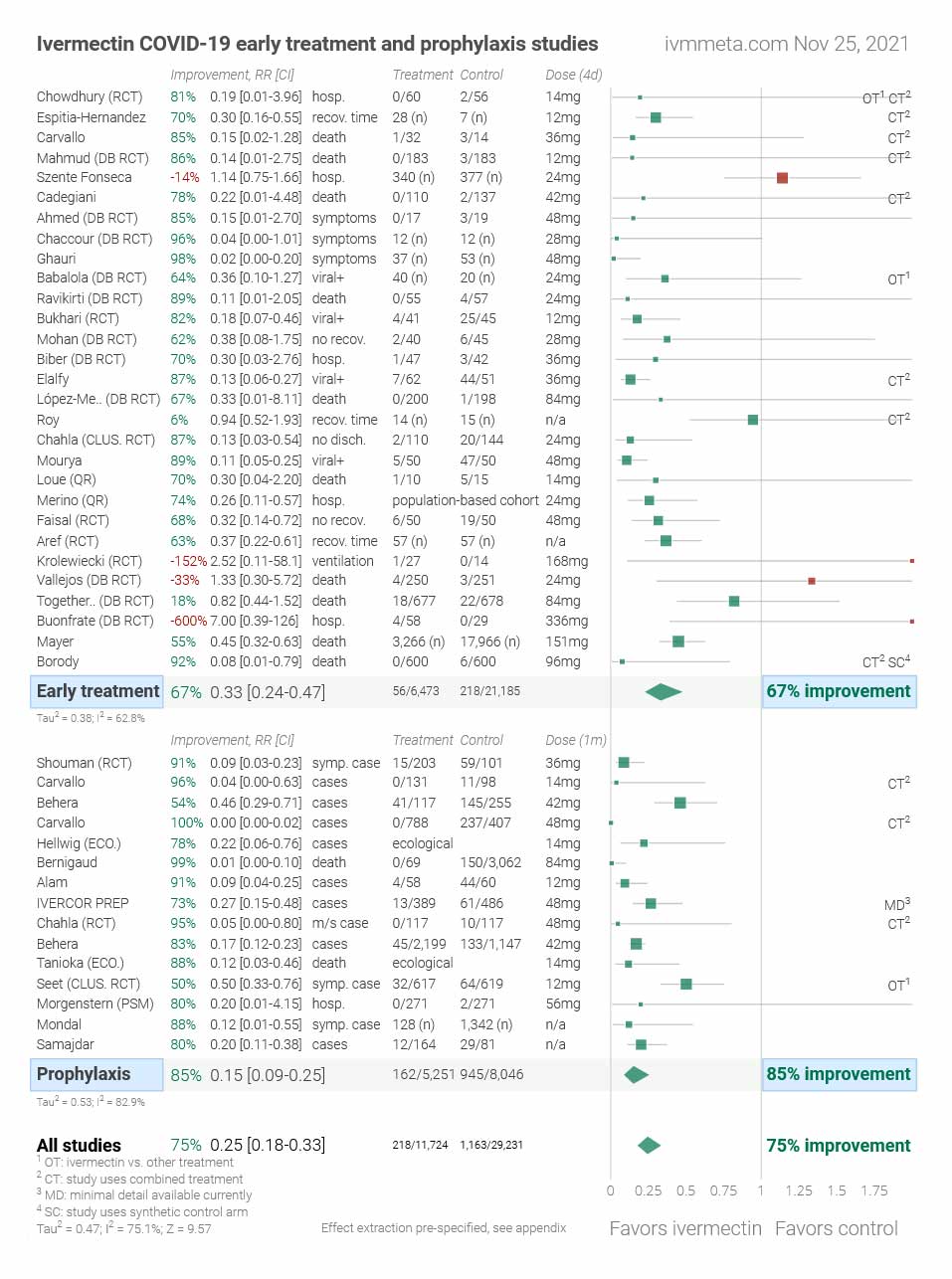

Ivermectin

Ivermectin is seen by some as the most promising alternative to vaccines available, but data regarding its efficacy in relation to preventing or treating COVID-19 has been highly contested.

Ivermectin was discovered in 1975 and developed as a new class of drug to treat parasitic infections. It was initially used in veterinary medicine, but approved for human use in 1987. The drug has been safely used to treat 3.7 billion people since the 1990s and distributed globally through mass drug administration campaigns against onchocerciasis (river blindness) and lymphatic filariasis (another disease caused by worms). It is currently listed on the WHO’s list of essential medicines.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) do not recommend ivermectin for use in routine management of COVID patients. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has said it has not authorised or approved ivermectin for use in preventing or treating COVID-19. Individuals seeking ivermectin without a prescription and misreporting has also led to significant controversy. Major pharmacy chains in the U.S. have begun refusing to fill patient perceptions for the drug if they have been prescribed for COVID-19 prophylaxis.

Dr. Pierre Kory is seen as one of the most prominent proponents of ivermectin. This is the most recent presentation by him I’ve found showing the evidence base supporting the efficacy of it in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

This is the only good instance I’ve found of Kory debating another scientist, Dr. Luis Garegnani, who wrote a paper critical of the current data and clinical evidence regarding ivermectin for treating COVID. This is the best analysis and criticism I’ve seen of Kory’s career and contributions in context of the most recent developments.

Criticisms of Ivermeta Data

Ivermeta has been one of the most cited resources by proponents of ivermectin. Scott Alexander’s article, Ivermectin: Much More Than You Wanted To Know, offers a critique and subsequent analysis of the state of the research surrounding Ivermectin. Scott’s findings are significant and imply many people have been wrong for different reasons. He says quite a bit about many other aspects of the pandemic which are also worth exploring. I highly recommend reading it verus taking in just this summary:

- Ivermectin doesn’t reduce mortality in COVID a significant amount (let’s say d > 0.3) in the absence of comorbid parasites: 85-90% confidence

- Parasitic worms are a significant confounder in some ivermectin studies, such that they made them get a positive result even when honest and methodologically sound: 50% confidence

- Fraud and data processing errors are of similar magnitude to p-hacking and methodological problems in explaining bad studies (95% confidence interval for fraud: between >1% and 5% as important as methodological problems; 95% confidence interval for data processing errors: between 5% and 100% as important)

- Probably “Trust Science” is not the right way to reach proponents of pseudoscientific medicine: ???% confidence

Alexandros Marinos wrote an detailed response to Scott’s article, A Conflict of Blurred Visions: A response on ivermectin to one of my heroes, Scott Alexander. It outlines a contrary perspective regarding Scott’s conclusions and the state of data related to ivermectin.

Sources:

Ivermectin: Much More Than You Wanted To Know by Scott Alexander – Astral Codex Ten – November 16, 2021

Types of Prophylaxis in Medicine – VeryWell Health – By Jennifer Whitlock – October 20, 2021

Ivermectin: From Soil to Worms, and Beyond – ISGlobal – November 21, 2019

COVID-19 early treatment: real-time analysis of 1,112 studies

What are the barriers to understanding?

There are a variety of barriers to our own understanding which we should factor or be aware of. Not all of these apply equally to everyone or to many people necessarily at all, but they can significantly alter our perceptions of all the other factors at a foundational level.

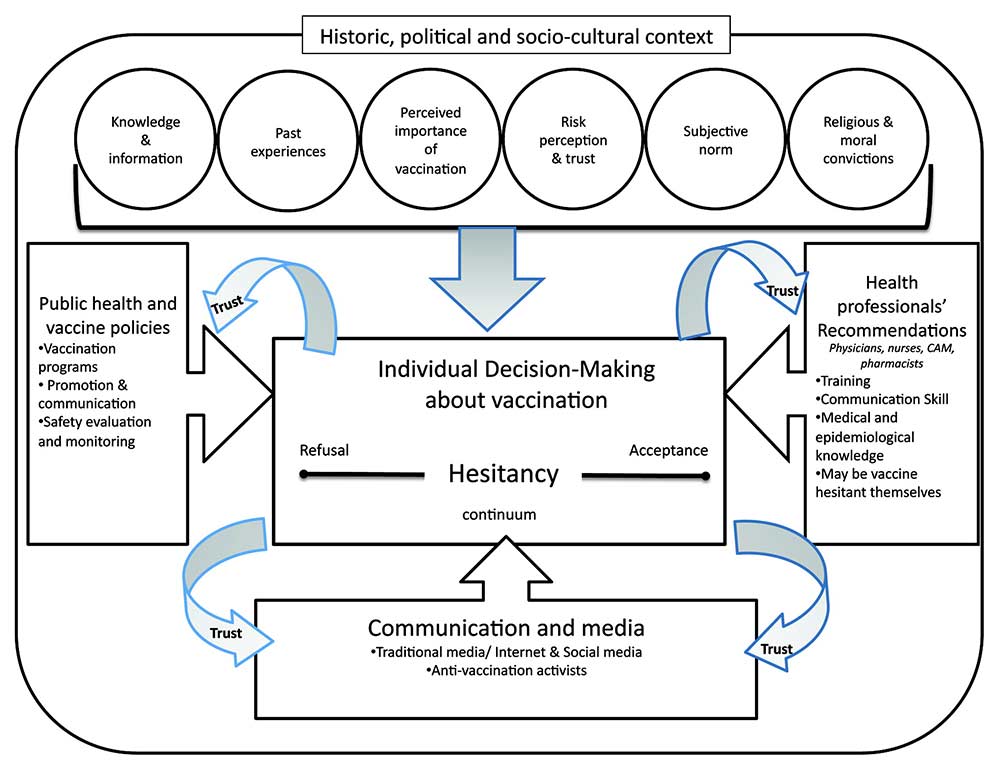

Hesitancy

Risk-aversion is a universal trait in humans, built from eons of evolution. Hesitancy can be helpful or harmful and is only a barrier in so much as our delay in making a decision may further expose us or others to potential risks. It can also allow us time to seek more information to make a better decision. It’s important to understand the nature of hesitancy related to vaccines, as a variety of studies have been done to attempt to model the most significant factors which affect individual decision making surrounding them specifically.

“Interpreting personal risk based on complex data can certainly be overwhelming. There is no absolute certainty in biology and medicine; that is for the pure mathematicians. Yet it is crucial to recognize that the same holds true for any applied science—including all the engineering that goes into constructing the buildings we live and work in, the cars we drive in, and the bridges we cross every day. It is natural and important to be concerned about safety, and there is no doubt that COVID-19 has caused an unprecedented disruption to our lives. But the right question to ask isn’t whether we have absolute certainty; it’s whether we have enough certainty.”

Andrew L. Croxford Ph.D – The Long-Term Safety Argument over COVID-19 Vaccines – Sept 14, 2021

Sources:

Vaccine hesitancy: An Overview – Published April 12, 2013

Are We Really Sure of mRNA Vaccine’s Long-term Safety? by Shin Jie Yong – November 7, 2021

Literacy

Scientific literacy refers to the level of reading and comprehension skills needed to comprehend general science information and news. It involves our knowledge and understanding of scientific concepts and the processes required for making personal health decisions. It’s more about our comprehension skills, versus our knowledge of specific scientific content or cumulative knowledge.

Vaccine literacy refers to the specific ability and skills for understanding information related to vaccines. It requires knowing how they work, the diseases they prevent, and their role in collective immunity. The broader notion of “health literacy” is also generally relevant and entails our ability, motivation, and competence to find, understand, and use health information.

Limitations or gaps in these forms of literacy affects our ability to take in and process information at the most basic levels. We should seek out quality sources of reliable information which can communicate to our levels of literacy while still aiming to continually improve our abilities for understanding.

Sources:

Effective Communications: The “Secret Sauce” for COVID-19 Vaccination – NFID – March 25, 2021

Assessing COVID-19 vaccine literacy: a preliminary online survey – July 5, 2020

Values

Our individual identity and values affect how significant a role science plays in our overall decision making. For example, one paper from 2012 found beliefs about climate change risks weren’t positively associated with scientific literacy, nor with measures of numeracy (our ability to comprehend quantitative information). The authors argued beliefs about climate change are largely determined by the values of the communities people identify with.

The role and significance science plays in our lives likely affects how effectively we can understand scientific concepts and information and then leverage it for personal and collective decisions. Scientific literacy is not isolated from our other beliefs, be they political, religious, epistemic, or otherwise. We should be conscious of the role science plays in our lives and how it might affect our overall ability to make effective and objective decisions in the real world, including in regard to COVID-19.

Source: Scientific Literacy: It’s Not (Just) About The Facts – NPR – September 14, 2015

Misinformation

Misinformation thrives in times of stress and uncertainty. We can’t tell exactly how impactful misinformation about COVID‐19 has been or will be, but the WHO has gone so far as to term the spread of it during the pandemic as an ‘infodemic’. This is the first pandemic to occur in the age of the internet and the overabundance of information online paired with the many unanswered questions related to COVID has led to a significant amount of misinformation surrounding it.

Defining misinformation is difficult and there is debate on whether there can be an objective set of criteria. Some researchers argue that for something to be considered misinformation it must go against “scientific consensus”. Although, notions of consensus opinion and scientific consensus are significantly different. Consensus implies agreement of the supermajority, not necessarily unanimous agreement, and that disagreement is limited or insignificant.

“[Scientific Consensus] is entirely predicated on evidence. A scientific consensus is not an opinion, survey, popularity contest, etc. among scientists. It is entirely dictated by the quality and quantity of evidence published in peer-reviewed journals. Further, the consensus is not absolute. In other words, being that scientists are an intellectually humble crowd, we are always open to the possibility that new evidence could potentially overturn the current consensus.”

Intelligent Speculation – Scientific Consensus by Jonathan Maloney – April 24, 2019

In 2021, Vivek Murthy, U.S. Surgeon General developed a comprehensive advisory exploring misinformation related to the pandemic. He defines misinformation as:

“Information that is false, inaccurate, or misleading according to the best available evidence at the time.”

He also states it’s important not to conflate controversial or unorthodox claims with misinformation. Some may attempt to categorize any false information as misinformation, but this can potentially broaden the definition in such a way as to diminish our collective ability to challenge information in general.

Critical thinking and general media literacy are important skills for reducing our susceptibility to misinformation. A disproportionate amount of people think they’re above average in terms of their ability to spot misinformation, meaning we should not overestimate our own abilities. The pandemic has also led to significant mental health issues resulting in people feeling confused, distressed, or mistrusting and made them more vaccine hesitant. Some research indicates that feeling anxious also makes people more willing to believe misinformation, even if it is inconsistent with their world views.

Sources:

COVID Case Study: Defining & Confronting Misinformation – The Communications Workshop LLC – October 31, 2021

Study Highlights What Makes COVID Misinformation So Tough to Stop on Social Media – NC State University – December 7, 2020

Bias

We all have a tendency to think in particular ways which can lead to systematic deviations or prevent us from making rational decisions. Cognitive biases have been studied for decades in fields such as cognitive science, social psychology, and behavioral economics. Being aware of biases, how they influence our decisions, and challenging them in ourselves and others are important steps to addressing them.

Throughout the pandemic, many have taken sides (e.g. pro-vax and anti-vax) and sought information they agree with or validated their existing bais and disregarded information which challenged it. Many have also leveraged social media and other online communities to reinforce or further amplify these biases.

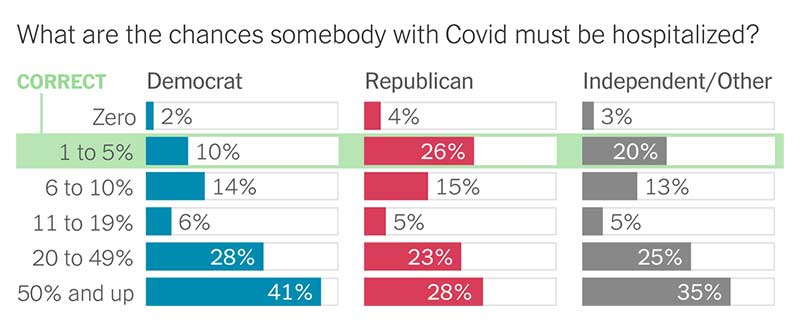

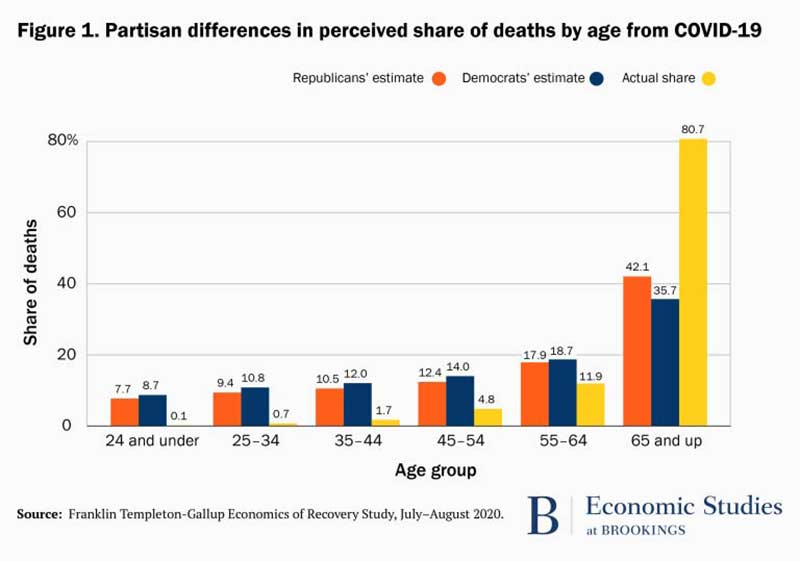

Our biases have significant potential to affect our overall perception of risks related to COVID-19. A survey of 35,000 Americans from July 2020 to December 2020 carried out by Gallup and Franklin Templeton showed significant misperceptions of the pandemic in both dominant political ideologies. Republican voters were more likely to underestimate the severity of COVID, whereas Democrats overestimated them.

The study showed the public at large has been significantly misinformed about the severity of the virus for the average person. Similar misconceptions were visible when participants were asked about the share of deaths between specific age groups.

Much of this data was collected during earlier phases of the pandemic, but there were many additional observations within the study which still make it a relevant example of biases being present. In August 2021, Gallup did a similar study with a smaller sample (3,158 people) showing a significant misperception of risk is likely still widespread among a majority of people.

These misperceptions are likely significant drivers of disagreement regarding the best responses to the pandemic, vaccines, masks, mandates, and many other decisions or policies.

Sources:

What Is Cognitive Bias? – Verywell Mind – May 5, 2020

Every Single Cognitive Bias in One Infographic by Jeff Desjardins – Visual Capitalist – August 26, 2021

COVID Case Study: Defining & Confronting Misinformation – Communications Workshop – Oct 31, 2021

COVID’s Partisan Errors by David Leonhardt – New York Times – May 19, 2021

How misinformation is distorting COVID policies and behaviors – Brookings – December 22, 2020

U.S. Adults’ Estimates of COVID-19 Hospitalization Risk – Gallup – September 27, 2021

Unknowns

There are multiple relevant factors we still do not have sufficient data on. Many are actively being studied and our understanding of them will evolve over time. Some are complex in ways we may never be able to sufficiently unravel or factor. Each of these should be considered important variables, however unknown.

What are the odds of reinfection?

Reinfection means a person was infected once, recovered, and then later became infected again. Scientists are still working to understand the many factors which affect the odds of COVD reinfection such as how likely it is currently, how long after the first infection it can take place, how severe such cases are, and who is at the highest risk.

One group of researchers attempted to model the odds of reinfection by referencing data from other known coronaviruses, such as those which cause Sars, MERS and the common cold. Their model suggests the average reinfection risk rises from about 5% four months after initial infection to 50% by 17 months.

“If we had no infection controls, no one was masking or social distancing, there were no vaccines, we should expect reinfection on a three-month to five-year timescale – meaning that the average person should expect to get COVID every three months to five years.”

Jeffrey Townsend, PhD and Professor at Yale School of Public Health – October 19, 2021

Another recent study followed 20,262 participants “at risk” of reinfection in the UK between July 2020 and September 2021. The study showed the estimated rate for all reinfections was 0.0118% or a rate of 11.8 per 100,000 participants.

Sources:

Reinfection with COVID-19 – CDC

Without COVID-19 jab, ‘reinfection may occur every 16 months’ – The Guardian – October 19, 2021

What are the odds of COVID becoming endemic?

“When cases are rising, more say the virus is here forever. When cases are dropping, people tend to believe it’s over. We’re all caught up in that still which makes objectivity harder to find.”

Andy Slavitt, the former White House Senior Advisor for COVID Response – August 14, 2021

An endemic disease is one which is always present in a certain population or region. Seasonal influenza and malaria are both common examples. Four seasonal coronaviruses circulate in humans endemically already and tend to recur annually, usually during the winter months.There is still no official or standard calculation for determining when a disease enters an endemic state, as it involves both objective and subjective factors. Not all experts, governments, or the general public agree on what constitutes an acceptable level of regular impact for diseases either, including COVID.

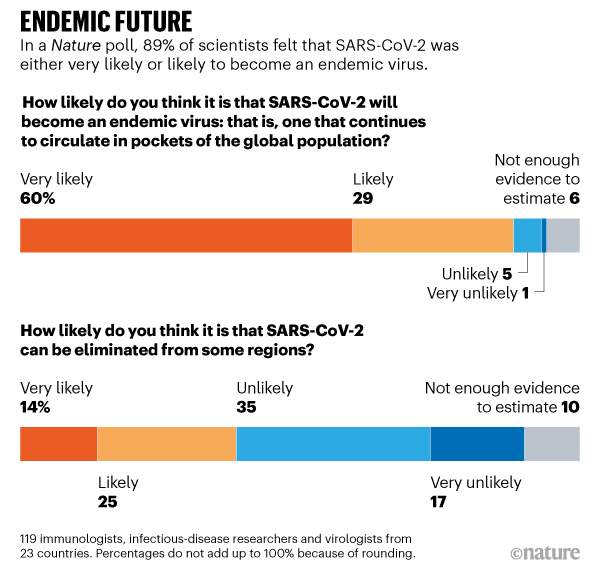

COVID-19 may transition into a set of predictable patterns over time, but is not yet considered to be endemic in any particular part of the world. In January 2021, Nature asked 119 immunologists, infectious-disease researchers, and virologists working on the coronavirus whether it would become endemic. 29% said it was likely and 60% said it was very likely.

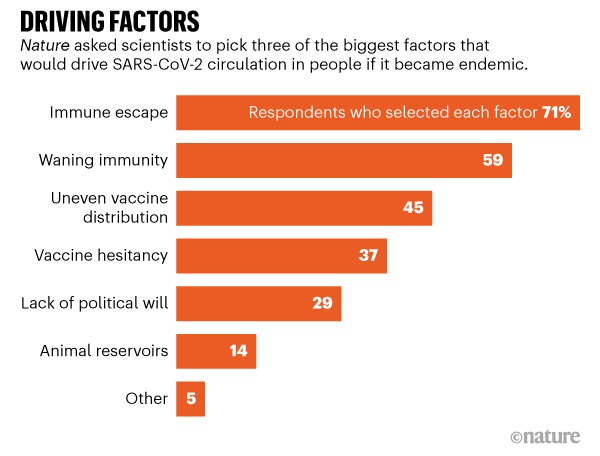

A variety of factors may drive COVID-19 towards an endemic state. Researchers from the same survey considered immune escape (71%) and waning immunity (59%) to be the two biggest driving factors.

Trevor Bedford is a computational virologist and professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle who has contributed significantly towards our understanding of the pandemic. On October 13, 2021 he gave a broad assessment of what he considers the ‘COVID endgame’ to currently look like. This is just one example from one virologist, but serves to show some of the various factors, nuances, and risks involved:

“I expect endemicity to be achieved at different times throughout the world due to inequities in vaccine distribution and I expect this to be a soft transition rather than a sudden flip of a switch.

However, even when the entire population of a region has immunity through infection or vaccination, there may still be significant circulation of the virus due to waning immunity and viral evolution.

As an example, seasonal influenza is an endemic respiratory virus and basically everyone over the age of ~3 will have immunity to it. However, despite this immunity, influenza infects ~10% of the adult population each year and causes perhaps 30k deaths per year in the US.

Broadly, I expect the eventual endemic state of COVID to be similar with substantial circulation but reduced disease burden relative to the pandemic state. The key parameters here include: 1. R0 2. Waning immunity 3. Antigenic drift 4. Infection to fatality rate (IFR)

R0 is the average number of secondary infections in a fully naive population. R0 of seasonal flu is around 2. R0 of Wuhan-like SARS-CoV-2 was around 3 and with Delta it’s now perhaps 5 or 6. Higher R0 should correspond to greater circulation all other things being equal.

Waning immunity is a bit more of an open question. Although other seasonal coronaviruses appear to cause reinfections every ~3 years, it’s hard to completely extrapolate from these viruses to SARS-like coronaviruses.

But based on what we’ve observed with waning immunity to infection in SARS-CoV-2, I think it’s safe to conclude there will be at least some waning of immunity to infection season-to-season in endemic state.

Although so far there’s been relatively little antigenic drift in SARS-CoV-2, we’ve seen rapid adaptive evolution in the S1 domain of spike protein as selection pressure has driven increased transmissibility.

Given the early emergence of partial immune escape in the Beta, Gamma and Mu variants and given the spike protein’s observed degree of adaptability, I would suspect that when selection pivots to be primarily immune driven we’ll see steady antigenic drift.

Recent adaptive evolution has been occurring at a significantly faster rate than H3N2 influenza, but my median scenario would be that with switch to endemicity, we see sustained antigenic evolution at a similar pace to influenza H3N2.

High R0, waning immunity and antigenic drift together suggest substantial seasonal circulation with a speculative guess of 20% or 30% of the population infected each year (often referred to as the “attack rate”). This is higher than flu due to R0 of ~6 rather than ~2.

At endemicity, circulation does not necessarily translate to disease burden. Based on robust vaccine effectiveness against severe outcomes, my speculative guess would be that infection to fatality rate (IFR) drops 10-fold from its original ~0.6% to a flu-like ~0.06%.

Together, this would suggest perhaps 40k or 100k deaths per year in the US from COVID at endemic state. Most infections would be relatively mild (just like flu), but there’s enough of them that even a small fraction of severe outcomes add up.

100k deaths would be 30% attack rate with 0.1% IFR, while 40k deaths would be 20% attack rate with 0.06% IFR. In general, like with seasonal flu I would expect significant season-to-season variability.

This is not cancer or heart disease, but it’s still a substantial public health burden. That said, yearly boosters just like flu vaccine, therapeutics like molnupiravir, improved ventilation and rapid testing can all contribute to reducing this ongoing burden.”

Sources:

The coronavirus is here to stay — here’s what that means by Nicky Phillips – Nature – February 16, 2021

Interview – Dr. Mike Ryan, EXO Who Health Emergencies Programme – November 4, 2021

Is COVID-19 here to stay? A team of biologists explains what it means for a virus to become endemic – University of Colorado Boulder – November 5, 2021

Eleanor Murray – epidemiologist at Boston University – Vox Interview – October 22, 2021

What will it be like when COVID-19 becomes endemic? – Harvard – August 11, 2021

What risks do variants pose?

All viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, mutate over time. Most mutations have little to no impact on the virus’ properties. However, some changes may affect how easily it spreads, severity of the disease (COVID-19), or the performance of vaccines, therapeutic medicines, diagnostic tools, and other public health measures.

Variants are classified in different categories by organizations such as the WHO and CDC. A Variant of Interest (VOI) is one which, compared to earlier forms of the virus, has genetic characteristics which predict greater transmissibility, evasion of immunity or diagnostic testing, or more severe disease. A variant of concern (VOC) is considered to be more infectious or more likely to cause breakthrough or re-infections in those who are vaccinated or previously infected. VOCs are more likely to cause severe disease, evade diagnostic tests, or resist antiviral treatment. Alpha, beta, gamma, and delta variants of the SARS-CoV-2 are all classified as VOCs.

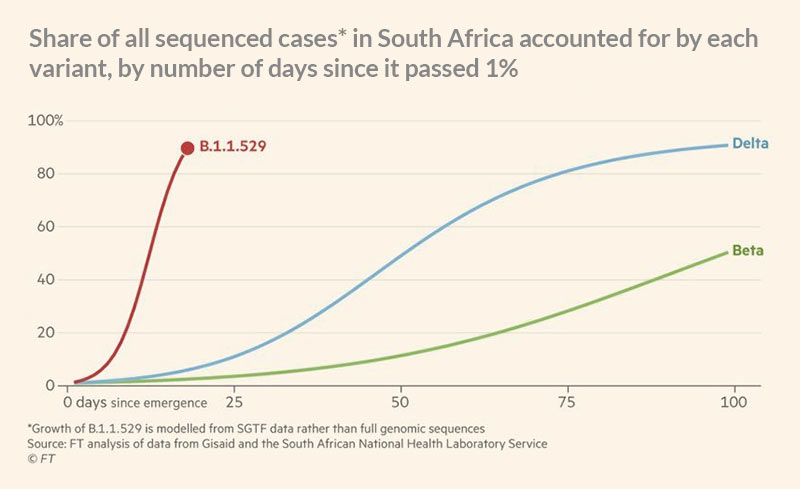

As of September 2021, delta has been regarded as the most contagious form of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus so far and currently accounts for 99.9% of cases in the United States. The Lambda and Mu variants are the two current variants of interest, according to the WHO. The potentials of these and future variants is unknown and still being studied, but the potential risks associated with more deadly or riskier variants should be factored.

Sources:

COVID Variants: What You Should Know – John Hopkins Medicine – October 5, 2021

CDC COVID Data Tracker – Variant Proportions

Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants – World Health Organization – Updated November 10, 2021

Omicron variant

On November 26, 2021 the WHO designated the B.1.1.529 strain, known as Omicron, a variant of concern. It was first identified in Botswana, South Africa. Not much is known about it yet, but it contains over thirty mutations to the spike protein found in other variants such as Delta and Alpha. Researchers are moving quickly to try to determine how transmissible it may be, likely to cause more severe disease, and have more immune escape properties.

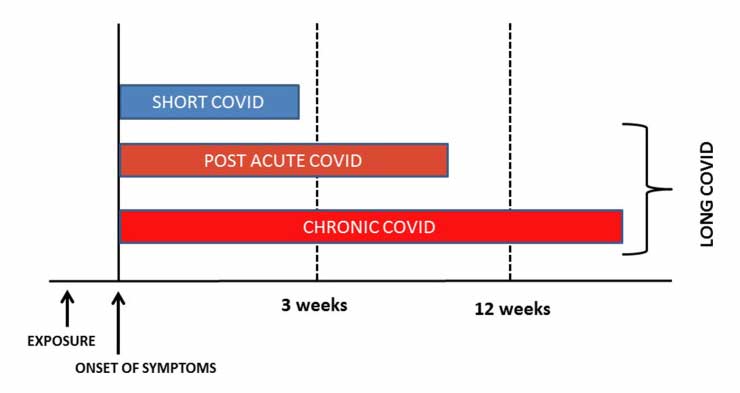

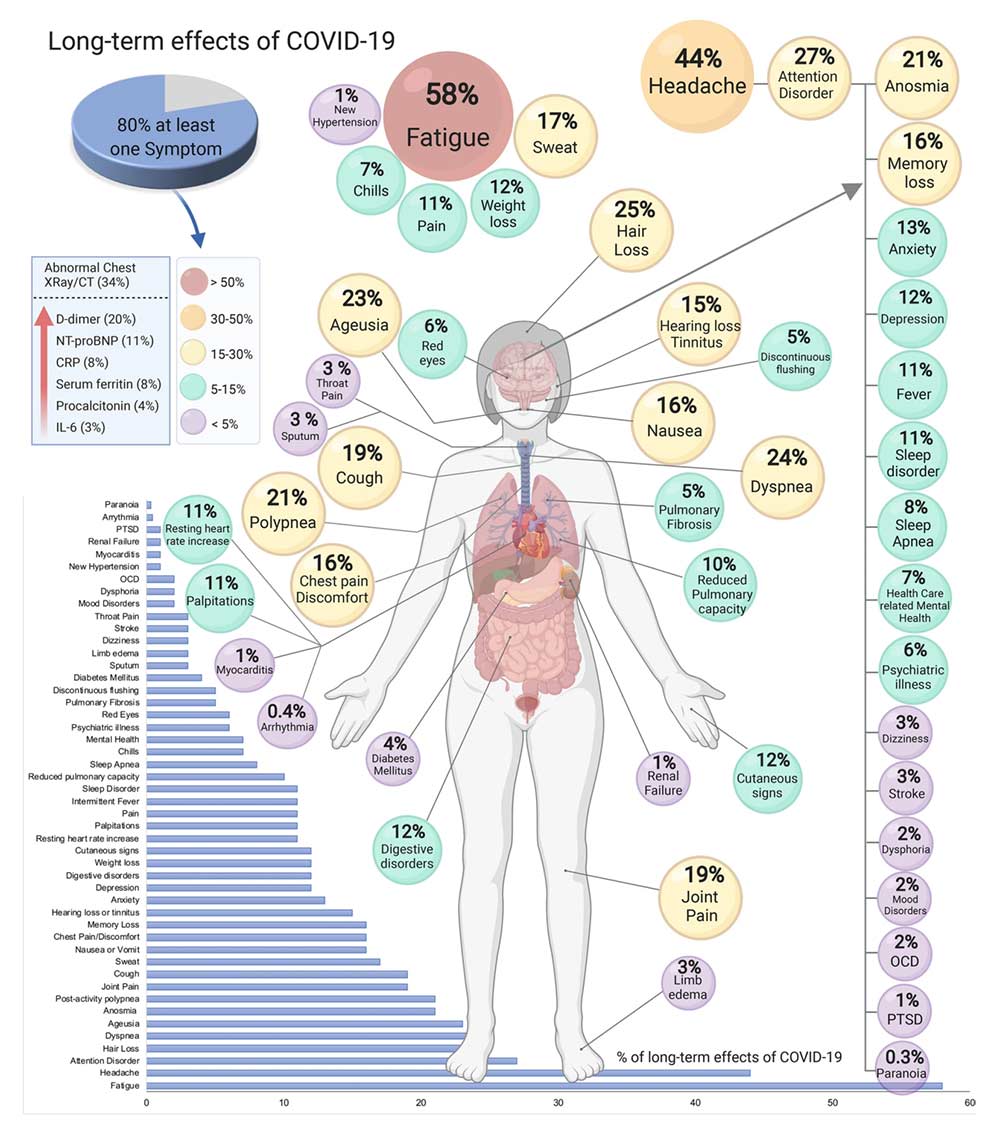

What are the risks of long COVID?

“A syndrome is a collection of symptoms of unclear causes, which is different from a disease with a defined set of symptoms and a cause. For example, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a disease of the lower respiratory tract that’s caused by a virus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In contrast, long-COVID is a syndrome involving multiple organ systems and biological causes.”

Shin Jie Yong – 9 Biological Explanations of Long-COVID Syndrome – October 26, 2021

UK-data from August 2021 showed 3% of people who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 experienced at least one continuous symptom 12–16 weeks after infection. If only symptomatic cases were counted, this percentage was 6.7%.

“One meta-analysis of 15 studies and one systematic review of 45 studies estimated 70-80% of COVID-19 survivors developed persistent symptoms representing long-COVID for weeks or months after the initial infection. But most of the reviewed studies did not have control groups to subtract the background rates of common long-COVID symptoms like fatigue. Even before the pandemic, 7–45% of the general population already has fatigue.

So, the true prevalence of long-COVID is probably 5–10% in survivors of mild COVID-19, which should be lesser in survivors of asymptomatic COVID-19 and higher in survivors of severe COVID-19.

Children can get long-COVID too, although the rate at which this occurs is still debated. Vaccinated people (with either Pfizer’s mRNA, Moderna’s mRNA, or AstraZeneca’s DNA vaccines; two doses) can also develop long-COVID, but this risk is 49% lower than unvaccinated people.”

Shin Jie Yong – 9 Biological Explanations of Long-COVID Syndrome – October 26, 2021

The potentials for long-COVID represent significant risks, even if they are still not well understood. Treatments are being developed and many studies are underway, but it’s uncertain how long symptoms could last, why some are able to recover when others don’t, and how effective treatments can potentially become.

Scott Alexander did a writeup of information related to long-COVID, Long COVID: Much More Than You Wanted To Know, on September 1, 2021. It’s an excellent overview of current research and one of the best I’m currently aware of.

Sources:

9 Biological Explanations of Long-COVID Syndrome – Shin Jie Yong – October 26, 2021

Long COVID: An overview – Published April 20, 2021

Long COVID – Wikipedia

Long-COVID symptoms can include fatigue, cough, chest tightness, breathlessness, palpitations, myalgia, and difficulty to focus. They can persist for months and range from mild to incapacitating, with new symptoms arising well after the time of infection.

What are the long-term risks of vaccines?

“Based on what we know, the answer is: aside from the slight possibility of long-term cardiovascular issues from the post-mRNA vaccine myocarditis, there’s no mechanism in which mRNA vaccines can cause problems months or years down the road.”

Shin Jie Yong – Are We Really Sure of mRNA Vaccine’s Long-term Safety? – November 7, 2021

Joomi Kim, a data scientist and former biologist, has written the best corollary I’m aware of. She covers some aspects or risks related to the spike protein, instances of neurological symptoms after vaccination, and outlines some boundaries of our understanding regarding the biological mechanisms of vaccines which have been inadequately distinguished in other contexts.

Sources:

Are We Really Sure of mRNA Vaccine’s Long-term Safety? – Shin Jie Yong – November 7, 2021

Clearing up misinformation about the spike protein and COVID vaccines – Joomi Kim – August 26, 2021

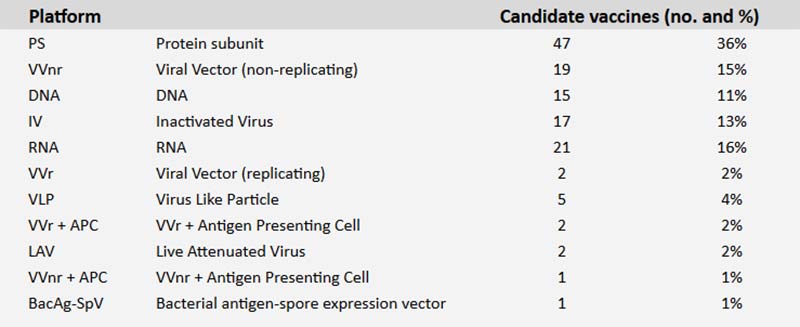

Are new vaccines being developed?

As of November 23, 2021, there are currently 194 vaccines in pre-clinical development and 132 in clinical development. Of those in clinical development, protein subunit is the most common platform (36%). Depending on the speed at which these are developed, tested, and the resulting risks and benefits, the range of options will change significantly over time.

The Novavax vaccine, a protein subunit vaccine developed by researchers in Maryland, is most likely to be the next available. The protein subunit approach used by Novavax was first implemented for the hepatitis B vaccine, which has been used in the U.S. since 1986. The technique uses moth cells to churn out spike proteins in bioreactors at low cost and the vaccine is able to be stored at normal temperatures, making it easier to replicate and distribute. The company has already filed for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) in some countries and a ruling is expected to be issued before the end of 2021.

Sources:

How the Novavax Vaccine Works – By Jonathan Corum and Carl Zimmer – New York Times – Updated May 7, 2021

The Second-Generation COVID Vaccines Are Coming by Zoe Cormier – Scientific American – January 20, 2021

What barriers are there to good data?

A variety of factors can prevent us from obtaining high quality information due to barriers at larger scales. Our barriers to understanding are individualized and can be known, whereas these barriers are less tangible and involve more complex relationships between larger systems or institutions. These barriers can affect our ability to make effective decisions even with us being fully aware of the possibilities related to them.

Scientism

The nature of science as it is performed and occurs through the individual mind is vastly different from the institutional reality of science and how it is conducted on an institutional scale. The interplay between science and governing bodies, politics, and other forms of authority is also complex. The limitations of science are not always a solid fit for leveraging them against every context as rapidly or confidently as some may be compelled to.

“We live in a mixed regime, an unstable hybrid of democratic and technocratic forms of authority. Science and popular opinion must be made to speak with one voice as far as possible, or there is conflict. According to the official story, we try to harmonise scientific knowledge and opinion through education. But in reality, science is hard, and there is a lot of it. We have to take it mostly on faith. That goes for most journalists and professors, as well as plumbers. The work of reconciling science and public opinion is carried out, not through education, but through a kind of distributed demagogy, or Scientism. We are learning that this is not a stable solution to the perennial problem of authority that every society must solve.

The phrase “follow the science” has a false ring to it. That is because science doesn’t lead anywhere. It can illuminate various courses of action, by quantifying the risks and specifying the tradeoffs. But it can’t make the necessary choices for us. By pretending otherwise, decision-makers can avoid taking responsibility for the choices they make on our behalf.”

How science has been corrupted by Matthew B Crawford – UnHerd – May 30, 2021

The synthesis of authorities within political and scientific contexts poses significant risks, such that the limitations of science are not fully considered or the findings of science are leveraged for political purposes and ends.

“Over the past year, a fearful public has acquiesced to an extraordinary extension of expert jurisdiction over every domain of life. A pattern of “government by emergency” has become prominent, in which resistance to such incursions are characterised as “anti-science”.

Henry H. Bauer, chemistry professor and former dean of arts and sciences at Virginia Tech, published a paper in 2004 in which he undertook to describe how science is actually conducted in the 21st century: it is, he says, fundamentally corporate (in the sense of being collective). “It remains to be appreciated that 21st-century science is a different kind of thing than the ‘modern science’ of the 17th through 20th centuries….”

Now, science is primarily organised around “knowledge monopolies” that exclude dissident views. They do so not as a matter of piecemeal failures of open-mindedness by individuals jealous of their turf, but systemically.”

How science has been corrupted by Matthew B Crawford – UnHerd – May 30, 2021

This culture of science makes it both more difficult to find good data as well as makes it more feasible for corporations to influence the spectrum of data and science. Ideologically, it can also result in us granting too much authority to scientists where or when we are unable or unwilling to effectively comprehend the limits and implications of doing so for ourselves.

“One of the most striking features of the present, for anyone alert to politics, is that we are increasingly governed through the device of panics that give every appearance of being contrived to generate acquiescence in a public that has grown skeptical of institutions built on claims of expertise. And this is happening across many domains. Policy challenges from outsiders presented through fact and argument, offering some picture of what is going on in the world that is rival to the prevailing one, are not answered in kind, but are met rather with denunciation. In this way, epistemic threats to institutional authority are resolved into moral conflicts between good people and bad people.

The spectacular success of “public health” in generating fearful acquiescence in the population during the pandemic has created a rush to take every technocratic-progressive project that would have poor chances if pursued democratically, and cast it as a response to some existential threat.

“Following the science” to minimise certain risks while ignoring others absolves us of exercising our own judgment, anchored in some sense of what makes life worthwhile. It also relieves us of the existential challenge of throwing ourselves into an uncertain world with hope and confidence. A society incapable of affirming life and accepting death will be populated by the walking dead, adherents of a cult of the demi-life who clamour for ever more guidance from experts.”

How science has been corrupted by Matthew B Crawford – UnHerd – May 30, 2021

Financial incentives & regulatory capture

“I still feel like I work for an evil corporation because it comes down to profits in the end. I mean, I’m there to help people, not to make millions and millions of dollars. So, I mean, that’s the moral dilemma.”

Chris Croce, Pfizer Senior Associate Scientist – Veritas – Undercover interview published Oct 4, 2021

There are significant financial incentives within the pharmaceutical industry. The vaccine market itself has been valued at $187 billion in 2021, with COVID-19 vaccines contributing $137 billion. Vaccines are one of the most powerful and cost-effective health interventions available and the benefits of COVID vaccines globally have been extremely significant. Although, the profit incentive, track records of manufacturers, corruption, and their relationships with governing and regulatory bodies represent a complex relationship which has historically generated and still generates significant barriers.

The FDA has gradually moved from an entirely taxpayer-funded entity to one increasingly funded by fees paid by the same companies it regulates. Close to 45% of its budget comes from fees companies pay when they apply for approval of a medical device or drug.

The nature and history of the pharmaceutical industry suffers from significant corruption in general. The industry overall has been fined over $50 billion in the last twenty years. Pfizer, for example, has paid billions in penalties for illegally marketing its drugs and bribing doctors in the past. The industry is also the largest lobbying body, outspending the second highest by almost double.

“The pharmaceutical industry spends more than any other industry on lobbying the US government, spending $280 million in 2018. The purpose of this is to ensure that there is very little regulation of the industry. The US regulator is called the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It is underfunded, has shown little interest in safety, and has no ongoing, long-term safety analysis. It also has serious conflicts of interest, with many staff connected to the industry. The former FDA chief went to work for the drug company, Pfizer. Many former members of the US congress have taken jobs as lobbyists for the pharmaceutical industry.”

The Crimes of the Pharmaceutical Industry – ElephantsInTheRoom – August 24, 2021

The same incentives and bureaucratic features de-incentivise pharmaceutical companies from pursuing approvals for generics. Some have made the claim this has been the case for ivermectin, as it has long been generic and originally showed some promise for early treatment of COVID.